It was mid-January in Western Washington, and the snow was coming down hard on my yurt seven miles up the mountain from town. The power was out, the roads were treacherous, and no end was in sight. It might have been my imagination, but I swore I heard all the wildlife trackers in the area shout in unison, “Perfect—let’s go!”

Once there was a break in the snowfall, a couple friends and I converged in the pristine whiteness to track on the Wilderness Awareness School’s land. Snow tracking is truly magical—we saw every bit of the morning pond activity, detailed on the ground like a meticulously kept journal. The main writer was my friend Ms. Lagomorph, known as Rabbit by those close to her.

Bound to be a Lagomorph

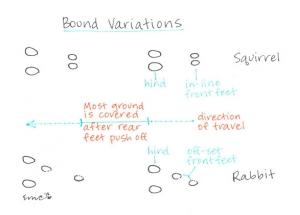

In a small clearing under the conifers near a pond outflow were dozens of similar crisscrossing trails. Even before stooping to examine a single track, my friends and I noticed the telltale track pattern—two offset smaller depressions, then two larger depressions in a horizontal line. After a gap, the pattern repeated. I closed my eyes and imagined an animal making these marks—two smaller feet landing one right after the other, then two larger feet landing at the same time and pushing off. In my mind’s eye, it certainly seemed like the bound of a rabbit or squirrel. By the large size, it was clear to me that it was not our diminutive Douglas squirrel. It had to be in the lagomorph (rabbit) family.

Another clue that it wasn’t a squirrel was that most squirrels display an in-line bound, the smaller front feet landing simultaneously in a horizontal line like the larger rear feet do. Because lagomorphs’ front feet land one after the other, their bound is called an offset bound.

Keep in mind that in very deep snow, a rabbit will launch itself up and forward, all four feet creating one large depression before it takes off again.

J is for Jumper

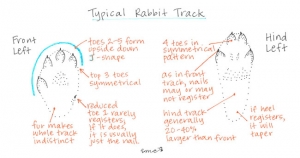

When I crouched down in the snow to sketch an individual track, it was difficult to distinguish any individual digits. This is par for the course; rabbit feet are heavily furred. I did find several clearer tracks which confirmed the basic elements of the front and hind rabbit tracks:

Keep in mind (as evidenced by the photos above) that often a rabbit track will only look like a couple of indistinct depressions and won’t contain the details in these drawings. That is why looking for a J-shape and the bounding track pattern is clutch.

Once you have identified tracks as those of a lagomorph, use your field guide to determine species. Measurements, habitat, and range maps are the best ways to distinguish species, though some have tracks that deviate more from the traditional rabbit pattern. The snowshoe hare, for example, has an even more heavily furred foot with widely splaying toes to give it that snowshoe effect.

Bunny Battles?

One thing that confused me as I followed Rabbit’s trails that day was several deep orange spots in the snow. Had our rabbits come to fisticuffs with the local raccoon gang? After some research, I discovered that rabbit urine can range from orange to red in color, most likely because of diet.

Now for a little scat-ercise. Imagine a large, slightly smushed pea. Now change the color from green to light brown and add texturing so that it looks as if the little ball is made of tiny fibers. Voila, rabbit scat! The rabbit scat I found in the clearing that day could have been mistaken for deer or rodent scat. Both deer and rodent scat tend to be elongated, while rabbit scat is round, typically from ¼ to ½ inches in diameter. Deer scat often is very smooth and sometimes has a nipple, while rabbit scat is un-nippled and has a wrinkled or fibrous quality. Rabbits ingest their first scats to obtain more nutrients, which gives their second scats (typically the only ones found in the wild) that fibrous, condensed appearance. The fibers are most prominent in winter scat due to all the woody cellulose lagomorphs ingest.

45 Snip, Not Grab and Rip

If you find a pile of rabbit scat, look closely around for feeding sign, since rabbits tend to deposit pellets singly unless they have been feeding for a long while in one area. Typical feeding sign in cold months is made with rabbit’s sharp upper and lower incisors. (Rabbits actually have four upper incisors, with two peg-like ones tucked behind the visible upper fronts. It is still not known what the purpose of the extra incisors are.) Rabbits snip a clean 45-degree angle from berry cane vines and hardwood twigs that are ½ inch or less in diameter. Snowshoe hares have been known to enjoy twigs and new growth from conifers as well. Rabbits do not climb, so look for sign around ground-level (or snowpack level). Deer feeding sign betrays the “rip and grab” method, because deer only have bottom incisors.

Rabbits also gnaw bark for nutrients. Voles, porcupines, and deer only feed to the cambium layer, usually in a much tidier fashion than rabbits, who eat into the wood itself. Warm weather feeding sign includes neatly snipped grasses and other herbivorous plants such as dandelion and clover. And of course, take the whole picture into account: tracks and scat in the area are big clues as to who has been feeding.

Now get out there and find yourself a bunny!