It was an early September morning in Western Washington, and I was slowly migrating from animal tracks and sign dreamland to reality. I had slept in the pasture next to my house, taking advantage of the last warm nights before the rain and cold set in. Hearing a rustle to my right, I opened my eyes to a beautiful sight: the slender, white, and tan neck of a black-tailed doe 5 feet away from me as she reached up toward a blackberry vine dangling from a tree. I could hear her tongue as she licked at the ripe berries, lapping them up like water. As I lay there for the next hour, invisible through stillness, I saw the almost-iridescent track of a slug trail across the doe’s coat (nighttime cuddle buddy?); I watched another doe join her to graze; I almost jumped up to frolic with two yearlings who came to stomp in the grass. And then I saw them all slip gracefully through the two middle fence slats, weaving their way into the darkness of the woods.

The black-tailed deer is a sub-species of the mule deer, inhabiting the western sides of British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and Northern California. As far as large wild animals go, deer are the animals that Regular Joe and Judy are most likely to see. Luckily, black-tailed deer are a rich source for learning about animal tracks and sign.

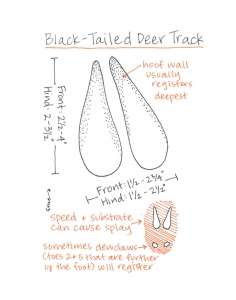

Heart-Shaped Hooves

Taken together, deer hooves resemble a heart with the bottom pointing in the direction of travel. The outside toe is slightly larger than the inside toe, and the front feet are larger than the hind feet (since more weight is carried in the front). In areas where their ranges overlap, white-tailed deer tracks are nearly impossible to distinguish from black-tailed deer without other non-track signs around.

Look for a track pattern that reflects a direct register walk, where the hindfoot lands directly where the front foot did. In forest litter, look for the signature “deer print rose” that results from leaves being pushed up like the petals of a rose.

Trails, Scat, and Lays—Oh My!

Young and old alike can get excited about finding and following deer runs. Deer trails are narrower than you’d imagine, often V-shaped, and fairly open vertically. Deer prefer to go around or under obstacles rather than over, and they can easily slide under branches as low as 2 feet.

Along deer runs, look for other deer sign. Deer scats are usually found in piles. Individual scats can be as small as a plum pit or as large as a peach pit. They are generally dark brown and cylindrical with one nippled end and one indented end, but can also be blunt or more amorphous.

While exploring the forest right next to a marsh recently, some students and I followed deer trails to a lovely scene: next to a large fallen tree and nestled into a couple of clumps of sword ferns was an oval about 2 feet wide by 3 feet long. The ferns and vegetation were heavily matted down, and there was scat nearby. A deer lay! Sometimes in snow you can even see the typical position a deer lays in: front legs tucked under the body (knees make an impression at the top of the oval), rear legs off to one side (making leg impressions on one side of the bottom of the oval.)

Bark Be Gone

For whatever reason, scraped off bark and missing branch ends excite me to no end. The possibilities are candy for my imagination: is this a bear climb, an antler rub, deer feeding sign, a cougar scrape, or my nephew fooling around with his new pocket knife? These nuggets of knowledge can help:

- The Ol’ Grab and Rip – Black-tailed deer love springtime for its tender grasses and summer for its low-growing leafy greens. In the winter, though, they move solely to browsing, which means eating bark, cambium, twigs, and shrubby leaves. Deer, like all other ruminants, have no upper incisors. This means that rather than giving plants a clean snip, they pull the ol’ grab and rip. If you see a twig that has been snipped at a clean 45-degree angle, you can assume it was not a deer but rather a rabbit or rodent. Look instead for a jagged, ripped edge at the height you’d assume a deer would be reaching.

- Cambium Feeding – Animals of all sizes feed on the inner bark (cambium layer) of trees. When looking at incisor marks, try to determine if the scraping is horizontal or vertical, if it is one-directional or two-directional, and how wide the incisors are. A deer would have to turn its head to the side (otherwise the snout would get in the way) and use one side of the lower incisors to scrape upwards only. Deer incisor marks usually are no wider than 3/16 of an inch. Deer incisor scrapes will most likely be no higher than 6 feet (depending on snowpack), but elk can go a foot and a half higher, and moose higher than that. Also, keep in mind the species of tree: mule deer love willow or alder.

- Antler Rubs – Deer grow new antlers every year that are covered with a velvety layer that they scrape off on small-diameter trees every fall during the mating season. Antler rubs may leave frayed bark which holds scent. For height comparisons among hoofed animals, just add about 8 inches to the estimations for an incisor scrape.

Deer: Gateway to a Tracking Obsession

Though the general public most likely knows what cougar and wolf tracks are via bumper stickers and football helmets, it is deer, in my opinion, who holds the most potential for unlocking the excitement of tracking for those who have no experience. With so many deer in today’s suburban areas, finding their track and sign is a treasure hunt that often leads to gold.

Sources:

Mammal Tracks and Sign by Mark Elbroch

Wild Animals of North America by the National Geographic Society

Behave: Stories of Applied Animal Behavior

Wildlife of the Pacific Northwest by David Moskowitz