Miss Part 1? Go here to read the first article.

Miss Part 1? Go here to read the first article.

Welcome back. Thanks for joining me once again. As you can see, bowmaking can be complex. That said, it is a craft that is well worth learning. Imagine shooting a bow that YOU made with your own hands. It is a feeling that cannot be described. Learning how to make a bow and arrow is something our ancestors intimately knew. So if you ever get overwhelmed, just remember that this is as much about the journey as it is the destination.

At the end of part one, your bow was in the drying stage. Once your bow is fully cured, you are ready to move on to the next step.

Laying Out Your Wood Bow

Tools: 72” straight edge, pencil, chalk-line, accurate 6” ruler

Up to this point, getting your bow “close-enough” is all that was needed. From here on out, it is important to be detail-oriented. The further along you get in the process of making a bow, the more critical it is to be focused.

Laying out your bow is an important stage. The layout will significantly impact your bow’s performance.

The major goals of laying out your bow are:

- Avoiding major flaws in your bow stave (knots, cracks, etc.)

- Aligning the tips with the handle (more on this later)

- Designing your bow for efficiency

How do they all work together?

Let’s start with length and width. For a bow that has a stiff handle section – often called a “D-bow” for its shape when fully drawn – you can expect to draw your bow to half the overall length of the bow. The average draw length is 28”.

So if you have a bow that is 60” long, then you could safely draw it to 30”. It’s nice to add a little extra length for safety’s sake. In general, a 68” bow is a good balance between safety and performance.

Another question on a lot of bowyer’s minds is, “How wide should my bow be?”

That depends on the density of wood AND the design. The denser the wood, the narrower you can make a bow.

Tangent alert: Most bowyers of the early 20th century believed that the only woods you could make a bow out of were osage orange, yew, and lemonwood. Why? Because the prevailing bow design was a narrow bow (1 ¼” wide). Only these ridiculously dense woods could tolerate being that narrow. But Native Americans were making bows out of dozens of different wood species. The trick: make the bow wider.

There are a lot of factors that determine how wide your bow should be. Let’s keep it simple for now. If you have a dense wood (hickory, black locust, elm, yew, osage orange), make your bow 1 ¾” wide. Anything that is less dense, widen it to 2”.

Here we go. If your bow stave is longer than 68”, then you have more room to lay out your bow. Take your straight edge and place it on your stave. Are there any knots? Are there any cracks (most likely near the ends of your bow)? Do your best to be strategic with your placement, avoiding any major problems. Start by marking the ends of where your 68” bow will be.

Earlier we talked about the importance of the tips being aligned with the bow handle. Think of when your bow has a string on it. It’s critical for your bow-string to be close to the center of the handle. This will allow our bow to be a smooth and consistent shooter.

Align your straight edge with the center of the bow. Now mark a vertical line:

- At 34” (the middle)

- 34” above the middle

- 34” below the middle

If your bow is straight, this will be a simple process. If it is wavy, then do your best to follow the grain of the wood as best you can. The most important thing is that these 3 points line up. You can actually make a bow out of very wavy wood – but it’s easiest to start with wood that is straight.

One tip: As you lay out your bow, try to make it as symmetrical as possible – working equally to the left and right of this center-line.

Let’s now lay out a handle in the middle of your bow. Mark a horizontal line at 34”. Your handle will be 1 ¼” wide and 1 ¼” deep and 4” long. Mark 2” above and below your center mark.

From the handle, you will transition from 1 ¼” wide to the full width of your bow. Take 2” of length to transition to the full 2” width (or whatever width you are choosing). Do this for your top and bottom limbs.

Looking at half the bow, we’ve now used 2” for the handle and 2” for the transition (also called the fades). We started with 34”, so we now have 30” to go.

Still with me?

For the next 15”, your bow will be a full 2” wide. Easy enough.

At this point, our bow is going to get narrower as we get closer to the tips. The bow tips do not need to take very much bend. And the less mass in the tips, the faster our bow will be.

So with 15” to go, narrow the tips from 2” down to ½”. The easiest way to do this is to start at the center-line of one tip. Mark ¼” on either side of this center-line. At 15” from the tip, where your bow is still 2” wide, use a 2’ straight edge (anything straight will work) to connect with the ¼” mark. Repeat on the other side.

When all is said and done, cut your bow to length and width. I often remove all of the wood just to the pencil lines. Use a bandsaw, drawknife, machete, or hewing hatchet to narrow your bow. Often I will leave the tips – the last 4” of the bow – a little wide (about ¾”). This allows for fine-tuning to get the string to lie as close to the center as possible.

The last step to lay out your wooden bow is to thin your bow stave. Leave it 1 ¼” thick for the center 4” (the handle). At the transitions, thin it gradually from 1 ¼” down to ¾” thick. This should leave plenty of thickness for tillering. “What is tillering?” you ask. I will tell you all about it.

How to Tiller a Wooden Bow

Up to this point, we have been learning the art of carpentry. But we are ready to take it to the next step: tillering.

Tillering is when we start to actually bend our bow. It will be gradual at first. The goal of tillering is to slowly remove wood from our bow so that:

1) Each limb takes an equal amount of strain

2) Each individual limb bends in a smooth arc

There are a few stages that we will proceed through:

- Floor tillering

- Tillering with a loose string

- Tillering with a tightened string

Before we bend our bow, it’s important to do one final preparation: smoothing the back of the bow. The back of the bow is where the outside of the tree was. If you haven’t removed the bark yet, it is time. Make sure to only remove bark, NOT actual wood. Do this slowly with a drawknife or other sharp tool.

For some woods, it is necessary to remove the sapwood (the lighter color wood on the outside of the tree). Osage orange and black locust are classic examples. This is beyond the scope of this article, but know that it is another essential step for certain woods.

Once the outer AND inner bark is removed, it’s time for sandpaper. Start with 60 grit, then 100, then 150, and finally 220 grit. The lower the number on the sandpaper, the rougher the grit. Go over the entire back of the bow with each grit in order from roughest to finest.

The last thing is to take a smooth glass bottle and burnish the back of the bow. Make sure the glass is completely smooth. You want to press down firmly. If you’ve done it correctly, your bow’s back will now look glossy!

Why are we doing all of this? Good question. Most bows tend to fail at weak spots on the back of bows. This could be a knot or simply a weak spot in the wood. By making a smooth, compressed surface we minimize this risk.

Floor Tillering

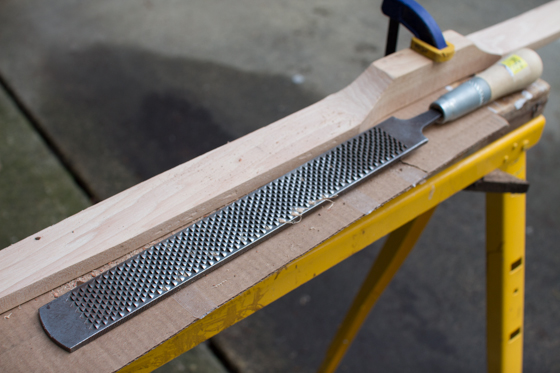

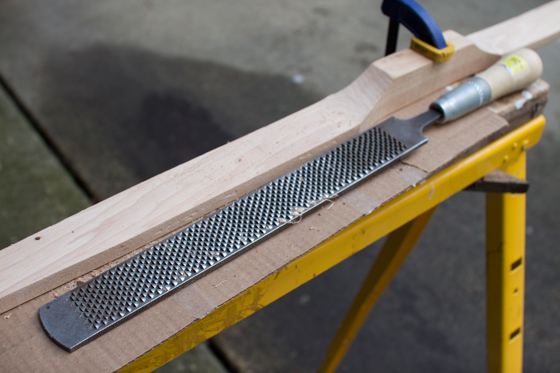

Tools: rasp, workbench/sawhorse, 2 clamps, patience

We are now finished with the back of the bow. From here on out, we only remove wood from the belly (the part of the bow you look at when shooting).

Let’s examine your workstation. Depending on your experience and your budget, you can go all out OR stick with the bare bones.

The most important component, as you start to remove wood more carefully, is a stable workstation. This can be a bench top, a sturdy picnic table , or even a sawhorse resting against a wall. If there is any movement in your setup, you will be wasting precious time and energy. I prefer to have the bow about level with my belly button. That way I can use my body weight without sacrificing my back.

My favorite tool at this stage is a ferrier’s rasp (designed for use on horse hooves). It is large, aggressive, and has a rasp side (teeth) and a file side (metal “lines”).

Clamp your bow to your workstation, using one clamp at the handle and one at the tip of the limb you are working on.

Your goal is to remove wood evenly only from the belly. Start near the handle and remove several passes working towards the tip. Right now you are just getting a feel for your tools and how much effort actually removes enough wood to show a difference in your bow’s bend. After about 30 passes on one side, remove an equal amount of wood on the other limb.

Unclamp your bow and perform the Floor Tiller test. Orient the bow so the belly is facing you. With your hand on the handle, place one limb tip on the ground (preferably not mud). Your other hand can be in the middle of the upper limb. With a smooth motion, bend the lower limb about an inch. Then come back to your original position. Repeat a couple of times and remember how it feels.

Now we are going to compare limbs. Repeat the same process on the other limb. Flip it over and see how it feels. Are they equal? Way different?

Ideally, your limbs are relatively close in how they feel when floor tillered. If they are unequal, then you want to remove wood from the “heavier” limb. If they are close, then you can work on both limbs, keeping them equal.

Now begins the journey of becoming proficient at using tools and making sure you are removing wood smoothly from the entire length of your bow. One common mistake I see is people making one side of the bow thinner than the other. This is likely caused by the way you are holding your rasp. I alternate between my left and right hand, to keep my muscles fresh and to balance out any bad habits that one hand might be exhibiting. Regardless, you want to check both sides of your bow very frequently.

Remove wood from both limbs, keeping them relatively equal in strength. I alternate between the rasp side and the file side because deep gouges from a ferrier’s rasp can be difficult to remove as you get farther along in your tillering.

Each time you remove wood, unclamp your bow and floor tiller both sides. If you are seeing lots of progress each time you remove wood, then you know you are being efficient. If nothing seems to be happening, know that you can be a little more aggressive.

The biggest thing to be aware of is removing wood evenly. If you look at the side profile of your bow, it should be flat. If you see dips and ridges and mini roller-coasters, STOP. Adjust your technique while there is still material on your bow. Take long, even passes. Push your rasp in line with the bow, instead of pushing perpendicular to the bow. Use long passes each time, instead of focusing too much on any one area.

When each bow limb is bending smoothly to about 3” AND the top and bottom limb feel equal to one another, it is time to add a string.

In How to Make a Bow and Arrow Part 3, we will look at Making a String, Creating String Grooves, and the Heart of Tillering.

Thanks for reading!